TINKER by Jerry Pournelle tells the story of a modern family with a home-based business among the stars.

TINKER by Jerry Pournelle tells the story of a modern family with a home-based business among the stars.

TINKER by Jerry Pournelle

A HUGO-nominated short story first published in GALAXY MAGAZINE, July 1975.

From the universe of HIGH JUSTICE

TINKER is an amazing time capsule for Pournelle family travel and contains many scenes that started on family road trips or high adventure Boy Scout outings led by Dr. P.

In our case, the ship was a 1976 International Harvester Scout, orange and white, with rear facing seats so the youngest could learn about motion sickness early on. It looked like you rented the thing from Uhaul and had all the creature comforts of a tractor. No matter if it was pulling a trailer with 6 canoes, held on it’s roof 14 backpacks and seated 10 boy scouts inside, it always got 12 miles-to-the-gallon. Usually we had to wait for the night sky before Jerry began with stories out among the stars.

Jerry indeed taught us all how to swear with humor and creative energy. “I will be dipped in sh*t!” usually started off a string of 8 or more cuss phrases including “Jesus Christmas on a stick” The insults for bad drivers were filled with obscure animals including the Quagga– a frighteningly dumb zebra from South Africa. Dangerous drivers that passed too fast or came dangerously close to the edge of a cliff anticipated the phrase ” Think of it as evolution in action” And God forbid if a kid was late climbing aboard after a pit stop. You learned ONCE that orders were to be obeyed.

The opening of TINKER comes from a bawdy rhymed drinking song, but it’s not the right song of our travels.

If Roberta wasn’t within earshot, we constantly begged to learn the “Ode to Eskimo Nelle“, which began in our version as “Oh when a man grows old and his b@lls grow cold, and the tip of his knob turns blue…” Yes, every 11 year old wanted to learn this bawdy rhymed drinking song to hear the tale of Deadeye Dick, his accomplice Mexican Pete and a woman they meet on their travels named Eskimo Nell.

Well that might be another story for later. This is a family story….

“THE TINKER CAME ASTRIDIN’, ASTRIDIN’ OVER THE

Strand, with his bullocks—”

“Rollo!”

“Yes, ma’am.” I’d been singing at the top of my lungs,

as I do when I’ve got a difficult piloting job, and I’d

forgotten that my wife was in the control cab. I went

back to the problem of setting our sixteen thousand

tons of ship onto the rock.

It wasn’t much of a rock. Jefferson is an irregular-

shaped asteroid about twice as far out as Earth. It

measures maybe seventy kilometers by fifty kilometers,

and from far enough away it looks like an old mud

brick somebody used for a shotgun target. It has a screwy

rotation pattern that’s hard to match with, and since I

couldn’t use the main engines, setting down was a tricky

job.

Janet wasn’t finished. “Roland Kephart, I’ve told you

about those songs.”

“Yeah, sure, hon.” There are two inertial platforms

in Slingshot, and they were giving me different readings.

We were closing faster than I liked.

“It’s bad enough that you teach them to the boys.

Now the girls are—”

I motioned toward the open intercom switch, and

Janet blushed. We fight a lot, but that’s our private

business.

The attitude jets popped. “Hear this,” I said. “I think

we’re coming in too fast. Brace yourselves.” The jets

popped again, short bursts that stirred up dust storms

on the rocky surface below. “But I don’t think—” the

ship jolted into place with a loud clang. We hit hard

enough to shake things, but none of the red lights came

on “—we’ll break anything. Welcome to Jefferson. We’re

down.”

Janet came over and cut off the intercom switch, and

we hugged each other for a second. “Made it again,”

she said, and I grinned.

There wasn’t much doubt on the last few trips, but

when we first put Slingshot together out of the wreckage

of two salvaged ships, every time we boosted out there’d

been a good chance we’d never set down again. There’s

a lot that can go wrong in the Belt, and not many ships

to rescue you.

I pulled her over to me and kissed her. “Sixteen years,”

I said. “You don’t look a day older.”

She didn’t, either. She still had dark red hair, same

color as when I met her at Elysium Mons Station on

Mars, and if she got it out of a bottle she never told me,

not that I’d want to know. She was wearing the same

thing I was, a skintight body stocking that looked as if

it had been sprayed on. The purpose was strictly func-

tional, to keep you alive if Slinger sprung a leak, but

on her it produced some interesting curves. I let my hands

wander to a couple of the more fascinating conic sections,

and she snuggled against me.

She put her head close to my ear and whispered

breathlessly, “Comm panel’s lit.”

“Bat puckey.” There was a winking orange light, show-

ing an outside call on our hailing frequency. Janet

handed me the mike with a wicked grin. “Lock up your

wives and hide your daughters, the tinker’s come to

town,” I told it.

“Slingshot, this is Freedom Station. Welcome back,

Cap’n Rollo.”

“Jed?” I asked.

“Who the hell’d you think it was?”

“Anybody. Thought maybe you’d fried yourself in the

solar furnace. How are things?” Jed’s an old friend. Like

a lot of asteroid Port Captains, he’s a publican. The

owner of the bar nearest the landing area generally gets

the job, since there’s not enough traffic to make Port

Captains a full-time deal. Jed used to be a miner in

Pallas, and we’d worked together before I got out of the

mining business.

We chatted about our families, but Jed didn’t seem as

interested as he usually is. I figured business wasn’t too

good. Unlike most asteroid colonies, Jefferson’s inde-

pendent. There’s no big corporation to pay taxes to, but

on the other hand there’s no big organization to bail

the Jeffersonians out if they get in too deep.

“Got a passenger this trip,” I said.

“Yeah? Rockrat?” Jed asked.

“Nope. Just passing through. Oswald Dalquist. Insur-

ance adjustor. He’s got some kind of policy settlement

to make here, then he’s with us to Marsport.”

There was a’long pause, and I wondered what Jed was

thinking about. “I’ll be aboard in a little,” he said. “Free-

dom Station out.”

Janet frowned. “That was abrupt.”

“Sure was.” I shrugged and began securing the ship.

There wasn’t much to do. The big work is shutting down

the main engines, and we’d done that a long way out

from Jefferson. You don’t run an ion engine toward an

inhabited rock if you care about your customers.

“Better get the big’uns to look at the inertial platforms,

hon,” I said. “They don’t read the same.”

“Sure. Hal thinks it’s the computer.”

“Whatever it is, we better get it fixed.” That would

be a job for the oldest children. Our family divides nicely

into the Big Ones, the Little Ones, and the Baby, with

various subgroups and pecking orders that Janet and I

don’t understand. With nine kids aboard, five ours and

four adopted, the system can get confusing. Jan and I

find it’s easier to let them work out the chain of com-

mand for themselves.

I unbuckled from the seat and pushed away. You

can’t walk on Jefferson, or any of the small rocks. You

can’t quite swim through the air, either. Locomotion is

mostly a matter of jumps.

As I sailed across the cabin, a big grey shape sailed

up to meet me, and we met in a tangle of arms and

claws. I pushed the tomcat away. “Damn it—”

“Can’t you do anything without cursing?”

“Blast it, then. I’ve told you to keep that animal out

of the control cab.”

“I didn’t let him in.” She was snappish, and for that

matter so was I. We’d spent better than six hundred

hours cooped up in a small space with just ourselves,

the kids, and our passenger, and it was time we had

some outside company.

The passenger had made it more difficult. We don’t

fight much in front of the kids, but with Oswald Dalquist

aboard the atmosphere was different from what we’re

used to. He was always very formal and polite, which

meant we had to be, which meant our usual practice of

getting the minor irritations over with had been ex-

changed for bottling them up.

Jan and I had a major fight coming, and the sooner it

happened the better it would be for both of us.

Slingshot is built up out of a number of compart-

ments. We add to the ship as we have to—and when

we can afford it. I left Jan to finish shutting down and

went below to the living quarters. We’d been down

fifteen minutes, and the children were loose.

Papers, games, crayons, toys, kids’ clothing, and books

had all more or less settled on the “down” side. Raquel,

a big bluejay the kids picked up somewhere, screamed

from a cage mounted on one bulkhead. The compart-

ment smelled of bird droppings.

Two of the kids were watching a TV program beamed

out of Marsport. Their technique was to push themselves

upward with their arms and float up to the top of the

compartment, then float downward again until they

caught themselves just before they landed. It took nearly

a minute to make a full circuit in Jefferson’s weak gravity.

I went over and switched off the set. The program was

a western, some horse opera made in the 1940’s.

Jennifer and Craig wailed in unison. “That’s educa-

tional, Dad.”

They had a point, but we’d been through this before.

For kids who’ve never seen Earth and may never go

there, anything about Terra can probably be educational,

but I wasn’t in a mood to argue. “Get this place cleaned

up.”

“It’s Roger’s turn. He made the mess.” Jennifer, being

eight and two years older than Craig, tends to be spokes-

man and chief petty officer for the Little Ones.

“Get him to help, then. But get cleaned up.”

“Yes, sir.” They worked sullenly, flinging the clothing

into corner bins, putting the books into the clips, and

the games into lockers. There really is a place for every-

thing in Slingshot, although most of the time you

wouldn’t know it.

I left them to their work and went down to the next

level. My office is on one side of that, balanced by the

“passenger suite” which the second oldest boy uses when

we don’t have paying customers. Oswald Dalquist was

just coming out of his cabin.

“Good morning, Captain,” he said. In all the time

he’d been aboard he’d never called me anything but

“Captain,” although he accepted Janet’s invitation to use

her first name. A very formal man, Mr. Oswald Dalquist.

“I’m just going down to reception,” I told him. “The

Port Captain will be aboard with the health officer in a

minute. You’d better come down, there will be forms

to fill out.”

“Certainly. Thank you, Captain.” He followed me

through the airlock to the level below, which was shops,

labs, and the big compartment that serves as a main en-

tryway to Slingshot.

Dalquist had been a good passenger, if a little distant.

He stayed in his compartment most of the time, did

what he was told, and never complained. He had very

polished manners, and everything he did was precise, as

if he thought out every gesture and word in advance.

I thought of him as a little man, but he wasn’t really.

I stand about six three, and Dalquist wasn’t a lot smaller

than me, but he acted little. He worked for Butterworth

Insurance, which I’d never heard of, and he said he was

a claims adjustor, but I thought he was probably an

accountant sent out because they didn’t want to send

anyone more important to a nothing rock like Jefferson.

Still, he’d been around. He didn’t talk much about

himself, but every now and then he’d let slip a story

that showed he’d been on more rocks than most people;

and he knew ship routines pretty well. Nobody had to

show him things more than once. Since a lot of life-

support gadgetry in Slingshot is Janet’s design, or mine,

and certainly isn’t standard, he had to be pretty sharp

to catch on so quick.

He had expensive gear, too. Nothing flashy, but his

helmet was one of Goodyear’s latest models, his skin-

tight was David Clark’s best with “stretch steel” threads

woven in with the nylon, and his coveralls were a special

design by Abercrombie & Fitch, with lots of gadget pock-

ets and a self-cleaning low-friction surface. It gave him a

pretty natty appearance, rather than the battered look

the old rockrats have.

I figured Butterworth Insurance must pay their adjus-

tors more than I thought, or else he had a hell of an ex-

pense account.

The entryway is a big compartment. It’s filled with

nearly everything you can think of: dresses, art objects,

gadgets and gizmos, spare parts for air bottles, sewing

machines, and anything else Janet or I think we can sell

in the way-stops we make with Slingshot. Janet calls it

the “boutique,” and she’s been pretty clever about what

she buys. It makes a profit, but like everything we do,

just barely.

I’ve heard a lot of stories about tramp ships making

a lot of money. Their skippers tell me whenever we meet.

Before Jan and I fixed up Slingshot I used to believe them.

Now I tell the same stories about fortunes made and

lost, but the truth is we haven’t seen any fortune.

We could use one. Hal, our oldest, wants to go to

Marsport Tech, and that’s expensive. Worse, he’s just the

first of nine. Meanwhile, Barclay’s wants the payments

kept up on the mortgage they hold on Slinger, fuel

prices go up all the time, and the big Corporations are

making it harder for little one-ship outfits like mine to

compete.

We got to the boutique just in time to see two figures

bounding like wallabies across the big flat area that serves

as Jefferson’s landing field. Every time one of the men

would hit ground he’d fling up a burst of dust that fell

like slow-motion bullets to make tiny craters around his

footsteps. The landscape was bleak, nothing but rocks

and craters, with the big steel airlock entrance to Free-

dom Port the only thing to remind you that several

thousand souls lived here.

We couldn’t see it, because the horizon’s pretty close

on Jefferson, but out beyond the airlock there’d be the

usual solar furnaces, big parabolic mirrors to melt down

ores. There was also a big trench shimmering just at the

horizon: ice. One of Jefferson’s main assets is water.

About ten thousand years ago Jefferson collided with

the head of a comet and a lot of the ice stayed aboard.

The two figures reached Slingshot and began the long

climb up the ladder to the entrance. They moved fast,

and I hit the buttons to open the outer door so they

could let themselves in.

Jed was at least twice my age, but like all of us who

live in low gravity it’s hard to tell just how old that is.

He has some wrinkles, but he could pass for fifty. The

other guy was a Dr. Stewart, and I didn’t know him.

There’d been another doctor, about my age, the last

time I was in Jefferson, but he’d been a contract man

and the Jeffersonians couldn’t afford him. Stewart was a

young chap, no more than twenty, born in Jefferson

back when they called it Grubstake and Blackjack Dan

was running the colony. He’d got his training the way

most people get an education in the Belt, in front of a

TV screen.

The TV classes are all right, but they have their limits.

I hoped we wouldn’t have any family emergencies here.

Janet’s a TV Doc, but unlike this Stewart chap she’s had

a year residency in Marsport General, and she knows the

limits of TV training. We’ve got a family policy that she

doesn’t treat the kids for anything serious if there’s an-

other doctor around, but between her and a new TV-

trained MD there wasn’t much choice.

“Everybody healthy?” Jed asked.

“Sure.” I took out the log and showed where Janet

had entered “NO COMMUNICABLE DISEASES” and signed

it.

Stewart looked doubtful. “I’m supposed to examine

everyone myself… .”

“For Christ’s sake,” Jed told him. He pulled at his

bristly mustache and glared at the young doc. Stewart

glared back. “Well, ’least you can see if they’re still

warm,” Jed conceded. “Cap’n Rollo, you got somebody

to take him up while we get the immigration forms taken

care of?”

“Sure.” I called Pam on the intercom. She’s second

oldest. When she got to the boutique, Jed sent Dr.

Stewart up with her. When they were gone, he took

out a big book of forms.

For some reason every rock wants to know your en-

tire life history before you can get out of your ship. I

never have found out what they do with all the infor-

mation. Dalquist and I began filling out forms while

Jed muttered.

“Butterworth Insurance, eh?” Jed asked. “Got much

business here?”

Dalquist looked up from the forms. “Very little. Per-

haps you can help me. The insured was a Mr. Joseph

Colella. I will need to find the beneficiary, a Mrs. Bar-

bara Morrison Colella.”

“Joe Colella?” I must have sounded surprised because

they both looked at me. “I brought Joe and Barbara

to Jefferson. Nice people. What happened to him?”

“Death certificate said accident.” Jed said it just that

way, flat, with no feeling. Then he added, “Signed by

Dr. Stewart.”

Jed sounded as if he wanted Dalquist to ask him

a question, but the insurance man went back to his

forms. When it was obvious that he wasn’t going to say

anything more, I asked Jed, “Something wrong with the

accident?”

Jed shrugged. His lips were tightly drawn. The mood

in my ship had definitely changed for the worse, and

I was sure Jed had more to say. Why wasn’t Dalquist

asking questions?

Something else puzzled me. Joe and Barbara were

more than just former passengers. They were friends

we were looking forward to seeing when we got to Jef-

ferson. I was sure we’d mentioned them several times

in front of Dalquist, but he’d never said a word.

We’d taken them to Jefferson about five Earth years

before. They were newly married, Joe pushing sixty

and Barbara less than half that. He’d just retired as a

field agent for Hansen Enterprises, with a big bonus

he’d earned in breaking up some kind of insurance

scam. They were looking forward to buying into the

Jefferson co-op system. I’d seen them every trip since,

the last time two years ago, and they were short of ready

money like everyone else in Jefferson, but they seemed

happy enough.

“Where’s Barbara now?” I asked Jed.

“Working for Westinghouse. Johnny Peregrine’s of-

fice.”

“She all right? And the kids?”

Jed shrugged. “Everybody helps out when help’s

needed. Nobody’s rich.”

“They put a lot of money into Jefferson stock,” I said.

“And didn’t they have a mining claim?”

“Dividends on Jefferson Corporation stock won’t even

r

pay air taxes.” Jed sounded more beat down than I’d

ever known him. Even when things had looked pretty

bad for us in the old days he’d kept all our spirits up

with stupid jokes and puns. Not now. “Their claim

wasn’t much good to start with, and without Joe to work

it—”

His voice trailed off as Pam brought Dr. Stewart

back into our compartment. Stewart countersigned the

log to certify that we were all healthy. “That’s it, then,”

he said. “Ready to go ashore?”

“People waitin’ for you in the Doghouse, Captain

Rollo,” Jed said. “Big meeting.”

“I’ll just get my hat.”

“If there is no objection, I will come too,” Dalquist

said. “I wonder if a meeting with Mrs. Colella can be

arranged?”

“Sure,” I told him. “We’ll send for her. Doghouse

is pretty well the center of things in Jefferson anyway.

Have her come for dinner.”

“Got nothing good to serve.” Jed’s voice was gruff with

a note of irritated apology.

“We’ll see.” I gave him a grin and opened the air-

lock.

There aren’t any dogs at the Doghouse. Jed had one

when he first came to Jefferson, which is why the

name, but dogs don’t do very well in low gravs. Like

everything else in the Belt, the furniture in Jed’s bar is

iron and glass except for what’s aluminum and titanium.

The place is a big cave hollowed out of the rock.

There’s no outside view, and the only things to look

at are the TV and the customers.

There was a big crowd, as there always is in the

Port Captain’s place when a ship comes in. More busi-

ness is done in bars than offices out here, which was

why Janet and the kids hadn’t come dirtside with me.

The crowd can get rough sometimes.

The Doghouse has a big bar running all the way

across on the side opposite the entryway from the main

corridor. The bar’s got a suction surface to hold down

anything set on it, but no stools. The rest of the big

room has tables and chairs and the tables have little

clips to hold drinks and papers in place. There are

also little booths around the outside perimeter for pri-

vacy. It’s a typical layout. You can hold auctions in

the big central area and make private deals in the

booths.

Drinks are served with covers and straws because

when you put anything down fast it sloshes out the

top. You can spend years learning to drink beer in low

gee if you don’t want to sip it through a straw or squirt

it out of a bulb.

The place was packed. Most of the cutomers were

miners and shopkeepers, but a couple of tables were

taken by company reps. I pointed out Johnny Peregrine

to Dalquist. “He’ll know how to find Barbara.”

Dalquist smiled that tight little accountant’s smile

of his and went over to Peregrine’s table.

There were a lot of others. The most important was

Habib al Shamlan, the Iris Company factor. He was

sitting with two hard cases, probably company cops.

The Jefferson Corporation people didn’t have a table.

They were at the bar, and the space between them

and the other Company reps was clear, a little island

of neutral area in the crowded room.

I’d drawn Jefferson’s head honcho. Rhoda Hendrix

was Chairman of the Board of the Jefferson Coporation,

which made her the closest thing they had to a govern-

ment. There was a big ugly guy with her. Joe Horn-

binder had been around since Blackjack Dan’s time.

He still dug away at the rocks, hoping to get rich. Most

people called him Horny for more than one reason.

It looked like this might be a good day. Everyone

stared at us when we came in, but they didn’t pay much

attention to Dalquist. He was obviously a feather mer-

chant, somebody they might have some fun with later

on, and I’d have to watch out for him then, but right

now we had important business.

Dalquist talked to Johnny Peregrine for a minute and

they seemed to agree on something because Johnny

nodded and sent one of his troops out. Dalquist went

over into a corner and ordered a drink.

There’s a protocol to doing business out here. I had

a table all to myself, off to one side of the clear area

in the middle, and Jed’s boy brought me a big mug of

beer with a hinged cap. When I’d had a good slug

I took messages out of my pouch and scaled them out

to people. Somebody bought me another drink, and

there was a general gossip about what was happen-

ing around the Belt.

AI Shamlan was impatient. After a half hour, which

is really rushing things for an Arab, he called across,

his voice very casual, “And what have you brought us,

Captain Kephart?”

I took copies of my manifest out of my pouch and

passed them around. Everyone began reading, but Johnny

Peregrine gave a big grin at the first item.

“Beef!” Peregrine looked happy. He had 500 workers

to feed.

“Nine tons,” I agreed.

“Ten francs,” Johnny said. “I’ll take the whole lot.”

“Fifteen,” al Shamlan said.

I took a big glug of beer and relaxed. Jan and I’d

taken a chance and won. Suppose somebody had flung

a shipment of beef into transfer orbit a couple of years

ago? A hundred tons could be arriving any minute, and

mine wouldn’t be worth anything.

Janet and I can keep track of scheduled ships, and

we know pretty well where most of the tramps like

us are going, but there’s no way to be sure about

goods in the pipeline. You can go broke in this racket.

There was more bidding, with some of the store-

keepers getting in the act. I stood to make a good

profit, but only the big corporations were bidding on

the whole lot. The Jefferson Corporation people hadn’t

said a word. I’d heard things weren’t going too well

for them, but this made it certain. If miners have any

money, they’ll buy beef. Beef tastes like cow. The stuff

you can make from algae is nutritious, but at best it’s

not appetizing, and Jefferson doesn’t even have the

plant to make textured vegetable proteins—not that

TVP is any substitute for the real thing.

Eventually the price got up to where only Iris and

Westinghouse were interested in the whole lot and I

broke the cargo up, seven tons to the big boys and

the rest in small lots. I didn’t forget to save out a

couple hundred kilos for Jed, and I donated half a ton

for the Jefferson city hall people to throw a feed with.

The rest went for about thirty francs a kilo.

That would just about pay for the deuterium I burned

up coming to Jefferson. There was some other stuff,

lightweight items they don’t make outside the big

rocks like Pallas, and that was all pure profit. I felt

pretty good when the auction ended. It was only the

preliminaries, of course, and the main event was what

would let me make a couple of payments to Barclay’s

on Slinger’s mortgage, but it’s a good feeling to know

you can’t lose money no matter what happens.

There was another round of drinks. Rockrats came

over to my table to ask about friends I might have run

into. Some of the storekeepers were making new deals,

trading around things they’d bought from me. Dalquist

came over to sit with me.

“Johnny finding your client for you?” I asked.

He nodded. “Yes. As you suggested, I have in-

vited her to dinner here with us.”

“Good enough. Jan and the kids will be in when

the business is over.”

Johnny Peregrine came over to the table. “Boosting

cargo this trip?”

“Sure.” The babble in the room faded out. It was

time to start the main event.

The launch window to Luna was open and would

be for another couple hundred hours. After that, the

fuel needed to give cargo pods enough velocity to put

them in transfer orbit to the Earth-Moon system would

go up to where nobody could afford to send down any-

thing massy.

There’s a lot of traffic to Luna. It’s cheaper, at the

right time, to send ice down from the Belt than it is

to carry it up from Earth. Of course, the Lunatics

have to wait a couple of years for their water to get

there, but there’s always plenty in the pipeline. Luna

buys metals, too, although they don’t pay as much as

Earth does.

“I’m ready if there’s anything to boost,” I said.

“I think something can be arranged,” al Shamlan said.

“Hah!” Hornbinder was listening to us from his place

at the bar. He laughed again. “Iris doesn’t have any

dee for a big shipment. Neither does Westinghouse. You

want to boost, you’ll deal with us.”

I looked to al Shamlan. It’s hard to tell what he’s think-

ing, and not a lot easier to read Johnny Peregrine, but

they didn’t look very happy. “That true?” I asked.

Hornbinder and Rhoda Hendrix came over to the

table. “Remember, we sent for you,” Rhoda said.

“Sure.” I had their guarantee in my pouch. Five

thousand francs up front, and another five thousand if

I got here on time. I’d beaten their deadline by twenty

hours, which isn’t bad considering how many million

kilometers I had to come. “Sounds like you’ve got a

deal in mind.”

She grinned. She’s a big woman, and as hard as the

inside of an asteroid. I knew she had to be sixty, but

she had spent most of that time in low gee. There wasn’t

much cheer in her smile. It looked more like the tomcat

does when he’s trapped a rat. “Like Horny says, we have

all the deuterium. If you want to boost for Iris and

Westinghouse, you’ll have to deal with us.”

“Bloody hell.” I wasn’t going to do as well out of

this trip as I’d thought.

Hornbinder grinned. “How you like it now, you god-

dam bloodsucker?”

“You mean me?” I asked.

“Fucking A. You come out here and use your god-

dam ship a hundred hours, and you take more than we

get for busting our balls a whole year. Fucking A, I

mean you.”

I’d forgotten Dalquist was at the table. “If you think

boostship captains charge too much, why don’t you

buy your own ship?” he asked.

“Who the hell are you?” Horny demanded.

Dalquist ignored him. “You don’t buy your own

ships because you can’t afford them. Ship owners have

to make enormous investments. If they don’t make

good profits, they won’t buy ships, and you won’t get

your cargo boosted at any price.”

He sounded like a professor. He was right, of course,

but he talked in a way that I’d heard the older kids

use on the little ones. It always starts fights in our fam-

ily and it looked like having the same result here.

“Shut up and sit down, Horny.” Rhoda Hendrix was

used to being obeyed. Hornbinder glared at Dalquist,

but he took a chair. “Now let’s talk business,” Rhoda

said. “Captain, it’s simple enough. We’ll charter your ship

for the next seven hundred hours.”

“That can get expensive.”

She looked to al Shamlan and Peregrine. They didn’t

look very happy. “I think I know how to get our money

back.”

“There are times when it is best to give in gracefully,”

al Shamlan said. He looked to Johnny Peregrine

and got a nod. “We are prepared to make a fair agree-

ment with you, Rhoda. After all, you’ve got to boost your

ice. We must send our cargo. It will be much cheaper for

all of us if the cargoes go out in one capsule. What are

your terms?”

‘‘No deal,” Rhoda said. “We’ll charter Cap’n Rollo’s

ship, and you deal with us.”

“Don’t I get a say in this?” I asked.

“You’ll get yours,” Hornbinder muttered.

Fifty thousand,” Rhoda said. “Fifty thousand to

charter your ship. Plus the ten thousand we promised

to get you here.”

“That’s no more than I’d make boosting your ice,” I

said. I usually get five percent of cargo value, and the

customer furnishes the dee and reaction mass. That ice

was worth a couple of million when it arrived at Luna.

Jefferson would probably have to sell it before then, but

even with discounts, futures in that much water would

sell at over a million new francs.

“Seventy thousand, then,” Rhoda said.

There was something wrong here. I picked up my beer

and took a long swallow. When I put it down, Rhoda

was talking again. “Ninety thousand. Plus your ten. An

even hundred thousand francs, and you get another

one percent of whatever we get for the ice after we sell

it.”

“A counteroffer may be appropriate,” al Shamlan said.

He was talking to Johnny Peregrine, but he said it

loud enough to be sure that everyone else heard him.

“Will Westinghouse go halves with Iris on a charter?”

Johnny nodded.

Al Shamlan’s smile was deadly. “Charter your ship to

us, Captain Kephart. One hundred and forty thousand

francs, for exclusive use for the next six hundred hours.

That price includes boosting a cargo capsule, provided

that we furnish you the deuterium and reaction mass.”

“One fifty. Same deal,” Rhoda said.

“One seventy five.”

“Two hundred.” Somebody grabbed her shoulder and

tried to say something to her, but Rhoda pushed him

away. “I know what I’m doing. Two hundred thousand.”

Al Shamlan shrugged. “You win. We can wait for the

next launch window.” He got up from the table. “Com-

ing, Johnny?”

“In a minute.” Peregrine had a worried look. “Ms.

Hendrix, how do you expect to make a profit? I assure

you that we won’t pay what you seem to think we will.”

“Leave that to me,” she said. She still had that look:

triumphant. The price didn’t seem to bother her at all.

“Hum.” A1 Shamlau made a gesture of bafflement.

“One thing, Captain. Before you sign with Rhoda, you

might ask to see the money. I would be much sur-

prised if Jefferson Corporation has two hundred thou-

sand.” He pushed himself away and sailed across the

bar to the corridor door. “You know where to find me

if things don’t work out, Captain Kephart.”

He went out, and his company cops came right after

him. After a moment Peregrine and the other corpora-

tion people followed.

I wonder what the hell I’d got myself into this time.

Rhoda Hendrix was trying to be friendly. It didn’t

really suit her style.

I knew she’d come to Jefferson back when it was

called Grubstake and Blackjack Dan was trying to set

up an independent colony. Sometime in her first year

she’d moved in with him, and pretty soon she was han-

dling all his financial deals. There wasn’t any nonsense

about freedom and democracy back then. Grubstake was

a big opportunity to get rich or get killed, and not much

more.

When they found Blackjack Dan outside without a

helmet, it turned out that Rhoda was his heir. She was

the only one who knew what kind of deals he’d made

anyway, so she took over his place. A year later she in-

vented the Jefferson Corporation. Everybody living on

the rock had to buy stock, and she talked a lot about

sovereign rights and government by the people. It takes

a lot of something to govern a few thousand rockrats,

and whatever it is, she had plenty. The idea caught on.

Now things didn’t seem to be going too well, and her

face showed it when she tried to smile. “Glad that’s

all settled,” she said. “How’s Janet?”

“The family is fine, the ship’s fine, and I’m fine,” I

said.

She let the phony grin fade out. “OK, if that’s the

way you want it. Shall we move over to a booth?”

“Why bother? I’ve got nothing to hide,” I told her.

“Watch it,” Hornbinder growled.

“And I’ve had about enough of him,” I told Rhoda.

“If you’ve got cargo to boost, let’s get it boosted.”

“In time.” She pulled some papers out of her pouch.

“First, here’s the charter contract.”

It was all drawn up in advance. I didn’t like it at all.

The money was good, but none of this sounded right.

“Maybe I should take al Shamlan’s advice and—”

“You’re not taking the Arab’s advice or their money

either,” Hornbinder said.

“—and ask to see your money first,” I finished.

“Our credit’s good,” Rhoda said.

“So is mine as long as I keep my payments up. I can’t

pay off Barclay’s with promises.” I lifted my beer and

flipped the top just enough to suck down a big gulp.

Beer’s lousy if you have to sip it.

“What can you lose?” Rhoda asked. “OK, so we don’t

have much cash. We’ve got a contract for the ice. Ten

percent as soon as the Lloyd’s man certifies the stuff’s

in transfer orbit. We’ll pay you out of that. We’ve got

the dee, we’ve got reaction mass, what the hell else do

you want?”

“Your radiogram said cash,” I reminded her. “I don’t

even have the retainer you promised. Just paper.”

“Things are hard out here.” Rhoda nodded to herself.

She was thinking just how hard things were. “It’s not

like the old days. Everything’s organized. Big companies.

As soon as we get a little ahead, the big outfits move in

and cut prices on everything we sell. Outbid us on every-

thing we have to buy. Like your beef.”

“Sure,” I said. “I’m facing tough competition from

the big shipping fleets, too.”

“So this time we’ve got a chance to hold up the big

boys,” Rhoda said. “Get a little profit. You aren’t hurt.

You get more than you expected.” She looked around to

the other miners. There were a lot of people listening to

us. “Kephart, all we have to do is get a little ahead, and

we can turn this rock into a decent place to live. A place

for people, not corporation clients!” Her voice rose and

her eyes flashed. She meant every word, and the others

nodded approval.

“You lied to me,” I said.

“So what? How are you hurt?” She pushed the con-

tract papers toward me.

“Excuse me.” Dalquist hadn’t spoken very loudly,

but everyone looked at him. “Why is there such a hurry

about this?” he asked.

“What the hell’s it to you?” Hornbinder demanded.

“You want cash?” Rhoda asked. “All right, I’ll give

you cash.” She took a document out of her pouch and

slammed it onto the table. She hit hard enough to raise

herself a couple of feet out of her chair. It would have

been funny if she wasn’t dead serious. Nobody laughed.

“There’s a deposit certificate for every goddam cent

we have!” she shouted. “You want it? Take it all. Take

the savings of every family in Jefferson. Pump us dry.

Grind the faces of the poor! But sign that charter!”

“Cause if you don’t,” Hornbinder said, “your ship

won’t ever leave this rock. And don’t think we can’t

stop you.”

“Easy.” I tried to look relaxed, but the sea of faces

around me wasn’t friendly at all. I didn’t want to look at

them so I looked at the deposit paper. It was genuine

enough: you can’t fake the molecular documents Zurich

banks use. With the Jefferson Corporation Seal and the

right signatures and thumbprints that thing was worth

exactly 78,500 francs.

It would be a lot of money if I owned it for myself. It

wasn’t so much compared to the mortgage on Stinger.

It was nothing at all for the total assets of a whole com-

munity.

“This is our chance to get out from under,” Rhoda was

saying. She wasn’t talking to me. “We can squeeze the

goddam corporation people for a change. All we need

is that charter and we’ve got Westinghouse and the Arabs

where we want them!”

Everybody in the bar was shouting now. It looked

ugly, and I didn’t see any way out.

“OK,” I told Rhoda. “Sign over that deposit certificate,

and make me out a lien on future assets for the rest.

I’ll boost your cargo—”

“Boost hell, sign that charter contract,” Rhoda said.

“Yeah, I’ll do that too. Make out the documents.”

“Captain Kephart, is this wise?” Dalquist asked.

“Keep out of this, you little son of a bitch.” Horny

moved toward Dalquist. “You got no stake in this. Now

shut up before I take off the top—”

Dalquist hardly looked up. “Five hundred francs to

the first man who coldcocks him,” he said carefully. He

took his hand out of his pouch, and there was a bill in

it.

There was a moment’s silence, then four big miners

started for Horny.

When it was over, Dalquist was out a thousand, be-

198

cause nobody could decide who got to Hornbinder first.

Even Rhoda was laughing after that was over. The

mood changed a little; Hornbinder had never been very

popular, and Dalquist was buying for the house. It didn’t

make any difference about the rest of it, of course. They

weren’t going to let me off Jefferson without signing that

charter contract.

Rhoda sent over to city hall to have the documents

made out. When they came, I signed, and half the

people in the place signed as witnesses. Dalquist didn’t

like it, but he ended up as a witness too. For better or

worse, Slingshot was chartered to the Jefferson Corpora-

tion for seven hundred hours.

The surprise came after I’d signed. I asked Rhoda

when she’d be ready to boost.

“Don’t worry about it. You’ll get the capsule when you

need it.”

“Bloody hell! You can’t wait to get me to sign—”

“Aww, just relax, Kephart.”

“I don’t think you understand. You have half a mil-

lion tons to boost up to what, five, six kilometers a sec-

ond?” I took out my pocket calculator. “Sixteen tons of

deuterium and eleven thousand reaction mass. That’s a

bloody big load. The fuel feed system’s got to be built.

It’s not something I can just strap on and push off—”

“You’ll get what you need,” Rhoda said. “We’ll let you

know when it’s time to start work.”

Jed put us in a private dining room. Janet came in

later and I told her about the afternoon. I didn’t think

she’d like it, but she wasn’t as upset as I was.

“We have the money,” she said. “And we got a good

price on the cargo, and if they ever pay off we’ll get

more than we expected on the boost charges. If they

don’t pay up—well, so what?”

“Except that we’ve got a couple of major companies

unhappy, and they’ll be here long after Jefferson folds

up. Sorry, Jed, but—”

He bristled his mustache. “Could be. I figure on gettin’

along with the corporations too. Just in case.”

“But what did all that lot mean?” Dalquist asked.

“Beats me.” Jed shook his head. “Rhoda’s been mak-

ing noises about how rich we’re going to be. New fur-

nace, another power plant, maybe even a ship of our

own. Nobody knows how she’s planning on doing it.”

“Could there have been a big strike?” Dalquist asked.

“Iridium, one of the really valuable metals?”

“Don’t see how,” Jed told him. “Look, mister, if

Rhoda’s goin’ to bail this place out of the hole the big

boys have dug for us, that’s great with me. I don’t ask

questions.”

Jed’s boy came in. “There’s a lady to see you.”

Barbara Morrison Colella was a small blonde girl,

pug nose, blue eyes. She looks like somebody you’d see

on Earthside TV playing a dumb blonde.

Her degrees said “family economics,” which I guess on

Earth doesn’t amount to much. Out here it’s a specialty.

To keep a family going out here you better know a lot of

environment and life-support engineering, something

about prices that depend on orbits and launch windows,

a lot about how to get something to eat out of rocks, and

maybe something about power systems, too.

She was glad enough to see us, especially Janet, but

we got another surprise. She looked at Dalquist and

said, “Hello, Buck.”

“Hello. Surprised, Bobby?”

“No. I knew you’d be along as soon as you heard.”

“You know each other, then,” I said.

“Yes.” Dalquist hadn’t moved, but he didn’t look like

a little man any longer. “How did it happen, Bobby?”

Her face didn’t change. She’d lost most of her smile

when she saw Dalquist. She looked at the rest of us, and

pointed at Jed. “Ask him. He knows more than I do.”

“Mr. Anderson?” Dalquist prompted. His tone made

it sound as if he’d done this before, and he expected to

be answered.

If Jed resented that, he didn’t show it. “Simple enough.

Joe always seemed happy enough when he came in here

after his shift—”

Dalquist looked from Jed to Barbara. She nodded.

“—until the last time. That night he got stinking

drunk. Kept mutterin’ something about ‘Not that way.

There’s got to be another way.’ ”

“Do you know what that meant?”

“No,” Jed said. “But he kept saying it. Then he got

really stinking and I sent him home with a couple of the

guys he worked with.”

“What happened when he got home?” Dalquist asked.

“He never came home, Buck,” Barbara said. “I got

worried about him, but T couldn’t find him. The men he’d

left here with said he’d got to feeling better and left

them—”

“Damn fools,” Jed muttered. “He was right out of it.

Nobody should go outside with that much to drink.”

“And they found him outside?”

“At the refinery. Helmet busted open. Been dead five,

six hours. Held the inquest right in here, at that table al

Shamlan was sitting at this afternoon.”

“Who held the inquest?” Dalquist asked.

“Rhoda.”

“Doesn’t make sense,” I said.

“No.” Janet didn’t like it much either. “Barbara, don’t

you have any idea of what Joe meant? Was he worried

about something?”

“Nothing he told me about. He wasn’t—-we weren’t

fighting, or anything like that. I’m sure he didn’t—”

“Humpf.” Dalquist shook his head. “What damned

fool suggested suicide?”

“Well,” Jed said, “you know how it is. If a man takes

on a big load and wanders around outside, it might as

well be suicide. Hornbinder said we were doing Barbara

a favor, voting it an accident.”

Dalquist took papers out of his pouch. “He was right,

of course. I wonder if Hornbinder knew that all Hansen

employees receive a paid-up insurance policy as one of

their retirement benefits?”

“I didn’t know it,” I said.

Janet was more practical. “How much is it worth?”

“I am not sure of the exact amounts,” Dalquist said.

“There are trust accounts involved also. Sufficient to get

Barbara and the children back to Mars and pay for their

living expenses there. Assuming you want to go?”

“I don’t know,” Barbara said. “Let me think about it.

Joe and I came here to get away from the big companies.

I don’t have to like Rhoda and the city hall crowd to

appreciate what we’ve got in Jefferson. Independence is

worth something.”

“Indeed,” Dalquist said. He wasn’t agreeing with her,

and suddenly we all knew he and Barbara had been

through this argument before. I wondered when.

“Janet, what would you do?” Barbara asked.

Jan shrugged. “Not a fair question. Roland and I

made that decision a long time ago. But neither of us is

alone.” She reached for my hand across the table.

As she said, we had made our choice. We’ve had

plenty of offers for Slingshot, from outfits that would be

happy to hire us as crew for Slinger. It would mean no

more hustle to meet the mortgage payments, and not a

lot of change in the way we live—but we wouldn’t be

our own people anymore. We’ve never seriously con-

sidered taking any of the offers.

“You don’t have to be alone,” Dalquist said.

“I know, Buck.” There was a wistful note in Barbara’s

voice. They looked at each other for a long time. Then

we sat down to dinner.

I was in my office aboard Slingshot. Thirty hours had

gone by since I’d signed the charter contract, and I still

didn’t know what I was boosting, or when. It didn’t make

sense.

Janet refused to worry about it. We’d cabled the

money on to Marsport, all of Jefferson’s treasury and

what we’d got for our cargo, so Barclay’s was happy for a

while. We had enough deuterium aboard Slinger to get

where we could buy more. She kept asking what there

was to worry about, and I didn’t have any answer.

I was still brooding about it when Oswald Dalquist

tapped on the door.

I hadn’t seen him much since the dinner at the

Doghouse, and he didn’t look any different, but he wasn’t

the same man. I suppose the change was in me. You

can’t think of a man named “Buck” the same way you

think of an Oswald.

“Sit down,” I said. That was formality, of course. It’s

no harder to stand than sit in the tiny gravity we felt.

“I’ve been meaning to say something about the way you

handled Horny. I don’t think I’ve ever seen anybody do

that.”

His smile was thin, and I guess it hadn’t changed

either, but it didn’t seem like an accountant’s smile any

more. “It’s an interesting story, actually,” he said. “A

long time ago I was in a big colony ship. Long passage,

nothing to do. Discovered the other colonists didn’t know

much about playing poker.”

We exchanged grins again.

“I won so much it made me worry that someone

would take it away from me, so I hired the biggest man

in the bay to watch my back. Sure enough, some chap

accused me of cheating, so I called on my big friend—”

“Yeah?”

“And he shouted ‘Fifty to the first guy that decks him.’

Worked splendidly, although it wasn’t precisely what I’d

expected when I hired him—”

We had our laugh.

“When are we leaving, Captain Kephart?”

“Beats me. When they get the cargo ready to boost, I

guess.”

“That might be a long time,” Dalquist said.

“What is that supposed to mean?”

“I’ve been asking around. To the best of my

knowledge, there are no preparations for boosting a big

cargo pod.”

“That’s stupid,” I said. “Well, it’s their business. When

we go, how many passengers am I going to have?”

His little smile faded entirely. “I wish I knew. You’ve

guessed that Joe Colella and I were old friends. And

rivals for the same girl.”

“Yeah. I’m wondering why you—hell, we talked

about them on the way in. You never let on you’d ever

heard of them.”

He nodded carefully. “I wanted to be certain. I only

know that Joe was supposed to have died in an accident.

He was not the kind of man accidents happen to. Not

even out here.”

“What is that supposed to mean?”

“Only that Joe Colella was one of the most careful

men you will ever meet, and I didn’t care to discuss my

business with Barbara until I knew more about the situ-

ation in Jefferson. Now I’m beginning to wonder—”

“Dad!” Pam was on watch, and she sounded excited.

The intercom box said again, “Dad!”

“Right, sweetheart.”

“You better come up quick. There’s a message coming

through. You better hurry.”

“MAYDAY MAYDAY MAYDAY.” The voice was

cold and unemotional, the way they are when they really

mean it. It rolled off the tape Pam had made.

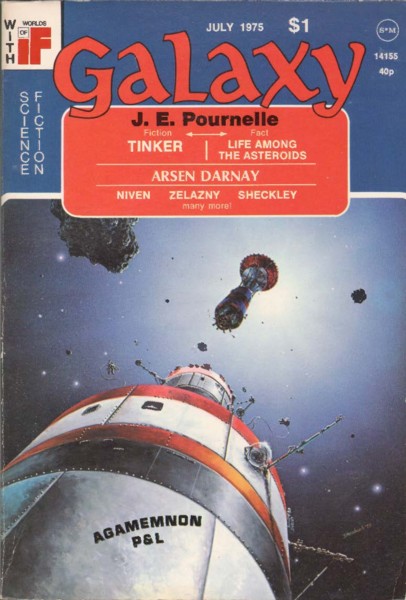

MAYDAY MAYDAY MAYDAY. THIS IS PEGASUS LINES

BOOSTSHIP AGAMEMNON OUTBOUND EARTH TO PAL-

LAS. OUR MAIN ENGINES ARE DISABLED. I SAY AGAIN,

MAIN ENGINES DISABLED. OUR VELOCITY RELATIVE

TO SOL IS ONE FOUR ZERO KILOMETERS PER SECOND,

I SAY AGAIN, ONE HUNDRED FORTY KILOMETERS PER

SECOND. AUXILIARY POWER IS FAILING. MAIN EN-

GINES CANNOT BE REPAIRED. PRESENT SHIP MASS IS

54,000 TONS. SEVENTEEN HUNDRED PASSENGERS

ABOARD. MAYDAY MAYDAY MAYDAY.

“Lord God.” I wasn’t really aware that I was talking.

The kids had crowded into the control cabin, and we

listened as the tape went on to give a string of numbers,

the vectors to locate Agamemnon precisely. I started to

punch them into the plotting tanks, but Pam stopped me.

“I already did that, Dad.” She hit the activation switch

to bring the screen to life.

It showed a picture of our side of the solar system, the

inner planets and inhabited rocks, along with a block of

numbers and a long thin line with a dot at the end to

represent Agamemnon. Other dots winked on and off:

boostships.

We were the only one that stood a prayer of a chance

of catching up with Agamemnon.

The other screen lit, giving us what the Register knew

about Agamemnon. It didn’t look good. She was an

enormous old cargo-passenger ship, over thirty years

old—and out here that’s old indeed. She’d been built for

a useful life of half that, and sold off to Pegasus Lines

when P&L decided she wasn’t safe.

Her auxiliary power was furnished by a plutonium

pile. If something went wrong with it, there was no way

to repair it in space. Without auxiliary power, the life-

support systems couldn’t function. I was still looking at

her specs when the comm panel lit. Local call, Port Cap-

tain’s frequency.

“Yeah, Jed?” I said.

“You’ve got the Mayday?”

“Sure. I figure we’ve got about sixty hours max to fuel

up and still let me catch her. I’ve got to try it, of course.”

“Certainly, Captain.” The voice was Rhoda’s. “I’ve

already sent a crew to start work on the fuel pod. I

suggest you work with them to be sure it’s right.”

“Yeah. They’ll have to work damned fast.” Slingshot

doesn’t carry anything like the tankage a run like this

would need.

“One more thing, Captain,” Rhoda said. “Remember

that your ship is under exclusive charter to the Jefferson

Corporation. We’ll make the legal arrangements with

Pegasus. You concentrate on getting your ship ready.”

“Yeah, OK. Out.” I switched the comm system to

Record. “Agamemnon, this is cargo tug Slingshot. I have

your Mayday. Intercept is possible, but I cannot carry

sufficient fuel and mass to decelerate your ship. I must

vampire your dee and mass, I say again, we must trans-

fer your fuel and reaction mass to my ship.

“We have no facilities for taking your passengers

aboard. We will attempt to take your ship in tow and

decelerate using your deuterium and reaction mass. Our

engines are modified General Electric Model five-niner

ion-fusion. Preparations for coming to your assistance

are under way. Suggest your crew begin preparations for

fuel transfer. Over.”

Then I looked around the cabin. Janet and our oldest

were ashore. “Pam, you’re in charge. Send that, and

record the reply. You can start the checklist for boost. I

make it about two-hundred centimeters acceleration, but

you’d better check that. Whatever it is, we’ll need to

secure for it. Also, get in a call to find your mother. God

knows where she is.”

“Sure, Dad.” She looked very serious, and I wasn’t

worried. Hal’s the oldest, but Pam’s a lot more thorough.

The Register didn’t give anywhere near enough data

about Agamemnon. I could see from the recognition pix

that she carried her reaction mass in strap-ons alongside

the main hull, rather than in detachable pods right

forward the way Slinger does. That meant we might have

to transfer the whole lot before we could start

deceleration.

She had been built as a general-purpose ship, so her

hull structure forward was beefy enough to take the

thrust of a cargo pod—but how much thrust? If we were

going to get her down, we’d have to push like hell on her

bows, and there was no way to tell if they were strong

enough to take it.

I looked over to where Pam was aiming our high-gain

antenna for the message to Agamemnon. She looked like

she’d been doing this all her life, which I guess she had

been, but mostly for drills. It gave me a funny feeling to

know she’d grown up sometime in the last couple of

years and Janet and I hadn’t really noticed.

“Pamela, I’m going to need more information on

Agamemnon,” I told her. “The kids had a TV cast out of

Marsport, so you ought to be able to get through. Ask for

anything they have on that ship. Structural strength,

fuel-handling equipment, everything they’ve got.”

“Yes, sir.”

“OK. I’m going ashore to see about the fuel pods. Call

me when we get some answers, but if there’s nothing im-

portant from Agamemnon just hang onto it.”

“What happens if we can’t catch them?” Philip asked.

Pam and Jennifer were trying to explain it to him as I

went down to the lock.

Jed had lunch waiting in the Doghouse. “How’s it

going?” he asked when I came in.

“Pretty good. Damned good, all things considered.”

The refinery crew had built up fuel pods for Slinger be-

fore, so they knew what I needed, but they’d never made

one that had to stand up to a full fifth of a gee. A couple

of centimeters is hefty acceleration when you boost big

cargo, but we’d have to go out at a hundred times that

“Get the stuff from Marsport?”

“Some of it.” I shook my head. The whole operation

would be tricky. There wasn’t a lot of risk for me, but

Agamemnon was in big trouble.

“Rhoda’s waiting for you. Back room.”

“You don’t look happy.”

Jed shrugged. “Guess she’s right, but it’s kind of

ghoulish.”

“What—?”

“Go see.”

Rhoda was sitting with a trim chap who wore a clipped

mustache. I’d met him before, of course: B. Elton, Esq.,

the Lloyd’s rep in Jefferson. He hated the place and

couldn’t wait for a transfer.

“I consider this reprehensible,” Elton was saying when

I came in. “I hate to think you are a party to this,

Captain Kephart.”

“Party to what?”

“Ms. Hendrix has asked for thirty million francs as

salvage fee. Ten million in advance.”

I whistled. “That’s heavy.”

“The ship is worth far more than that,” Rhoda said.

“If I can get her down. There are plenty of problems

—hell, she may not be fit for more than salvage,” I said.

“Then there are the passengers. How much is Lloyd’s

out if you have to pay off their policies? And lawsuits?”

Rhoda had the tomcat’s grin again. “We’re saving you

money, Mr. Elton.”

I realized what she was doing. “I don’t know how to

say this, but it’s my ship you’re risking.”

“You’ll be paid well,” Rhoda said. “Ten percent of

what we get.”

That would just about pay off the whole mortgage. It

was also a hell of a lot more than the commissioners in

Marsport would award for a salvage job.

“We’ve get heavy expenses up front,” Rhoda was say-

ing. “That fuel pod costs like crazy. We’re going to miss

the launch window to Luna.”

“Certainly you deserve reasonable compensation,

but—”

“But nothing!” Rhoda’s grin was triumphant. “Captain

Kephart can’t boost without fuel, and we have it all. That

fuel goes aboard his ship when you’ve signed my

contract, Elton, and not before.”

Elton looked sad and disgusted. “It seems a cheap—”

“Cheap!” Rhoda got up and went to the door. “What

the hell do you know about cheap? How goddamn many

times have we heard you people say there’s no such

thing as an excess profit? Well, this time we got the

breaks, Elton, and we’ll take the excess profits. Think

about that.”

Out in the bar somebody cheered. Another began

singing a tune I’d heard in Jefferson before. Pam

says the music is very old, she’s heard it on TV casts,

but the words fit Jefferson. The chorus goes “There’s

gonna be a great day!” and everybody out there shouted it.

“Marsport will never give you that much money,”

Elton said.

“Sure they will.” Rhoda’s grin got even wider, if that

was possible. “We’ll hold onto the cargo until they do—”

“Be damned if I will!” I said.

“Not you at all. I’m sending Mr. Hornbinder to take

charge of that. Don’t worry, Captain Kephart, I’ve got

you covered. The big boys won’t bite you.”

“Hornbinder?”

“Sure. You’ll have some extra passengers this run—”

“Not him. Not in my ship,” I said.

“Sure he’s going. You can use some help—”

Like hell. “I don’t need any.”

She shrugged. “Sorry you feel that way. Just remem-

ber, you’re under charter.” She gave the tomcat grin

again and left.

When she was gone, Jed came in with beer for me

and something else for Elton. They were still singing

and cheering in the other room.

“Do you think this is fair?” Elton demanded.

Jed shrugged. “Doesn’t matter what I think. Or what

Rollo thinks. Determined woman, Rhoda Hendrix.”

“You’d have no trouble over ignoring that charter

contract,” Elton told me. “In fact, we could find a rea-

sonable bonus for you—”

“Forget it.” I took the beer from Jed and drank it all.

Welding up that fuel pod had been hot work, and I

was ready for three more. “Listen to them out there,”

I said. “Think I want them mad at me? They see this as

the end of their troubles.”

“Which it could be,” Jed said. “With a few million

to invest we can make Jefferson into a pretty good

place.”

Elton wasn’t having any. “Lloyd’s is not in the busi-

ness of subsidizing colonies that cannot make a living—”

“So what?” I said. “Rhoda’s got the dee and nobody

else has enough. She means it, you know.”

“There’s less than forty hours,” Jed reminded him. “I

think I’d get on the line to my bosses, was I you.”

“Yes.” Elton had recovered his polish, but his eyes

were narrow. “I’ll just do that”

They launched the big fuel pod with strap-on solids,

just enough thrust to get it away from the rock so I

could catch it and lock on. We had hours to spare, and I

took my time matching velocities. Then Hal and I went

outside to make sure everything was connected right.

Hornbinder and two friends were aboard against all

my protests. They wanted to come out with us, but I

wasn’t having any. We don’t need help from ground-

pounders. Janet and Pam took them to the gallery for

coffee while I made my inspection.

Slingshot is basically a strongly built hollow tube with

engines at one end and clamps at the other. The cab-

ins are rings around the outside of the tube. We also

carry some deuterium and reaction mass strapped on to

the main hull, but for big jobs there’s not nearly enough

room there. Instead, we build a special fuel pod that

straps onto the bow. The reaction mass can be lowered

through the central tube when we’re boosting.

Boost cargo goes on forward of the fuel pod. This time

we didn’t have any going out, but when we caught up to

Agamemnon she’d ride there, no different from any

other cargo capsule. That was the plan, anyway. Taking

another ship in tow isn’t precisely common out here.

Everything matched up. Deuterium lines, and the ele-

vator system for handling the mass and getting it into the

boiling pots aft; it all fit. Hal and I took our time, even

after we were sure it was working, while the Jefferson

miners who’d come up with the pod fussed and worried.

Eventually I was satisfied, and they got onto their bikes

to head for home. I was still waiting for a call from

Janet.

Just before they were ready to start up she hailed us.

She used an open frequency so the miners could hear.

“Rollo, I’m afraid those crewmen Rhoda loaned us will

have to go home with the others.”

“Eh?” One of the miners turned around in the sad-

dle.

“What’s the problem, Jan?” I asked.

“It seems Mr. Hornbinder and his friends have very

bad stomach problems. It could be quite serious. I think

they’d better see Dr. Stewart as soon as possible.”

“Goddam. Rhoda’s not going to like this,” the foreman

said. He maneuvered his little open-frame scooter over

to the airlock. Pam brought his friends out and saw

they were strapped in.

“Hurry up!” Hornbinder said. “Get moving!”

“Sure, Horny.” There was a puzzled note in the fore-

man’s voice. He started up the bike. At maximum

thrust it might make a twentieth of a gee. There was no

enclosed space, it was just a small chemical rocket with

saddles, and you rode it in your suit.

“Goddamit, get moving,” Hornbinder was shouting. If

there’d been air you might have heard him a klick away.

“You can make better time than this!”

I got inside and went up to the control cabin. Jan was

grinning.

“Amazing what calomel can do,” she said.

“Amazing.” We took time off for a quick kiss be-

fore I strapped in. I didn’t feel much sympathy for

Horny, but the other two hadn’t been so bad. The one to

feel sorry for was whoever had to clean up their suits.

Ship’s engines are complicated things. First you take

deuterium pellets and zap them with a big laser. The dee

fuses to helium. Now you’ve got far too much hot gas at

far too high a temperature, so it goes into an MHD

system that cools it and turns the energy into electricity.

Some of that powers the lasers to zap more dee. The

rest powers the ion drive system. Take a metal, pre-

ferably something with a low boiling point like cesium,

but since that’s rare out here cadmium generally has to

do. Boil it to a vapor. Put the vapor through ionizing

screens that you keep charged with power from the fu-

sion system.

Squirt the charged vapor through more charged plates

to accelerate it, and you’ve got a drive. You’ve also got

a charge on your ship, so you need an electron gun to

get rid of that.

There are only about nine hundred things to go

wrong with the system. Superconductors for the mag-

netic fields and charge plates: those take cryogenic sys-

tems, and those have auxiliary systems to keep them

going. Nothing’s simple, and nothing’s small, so out of

Slingshot’s sixteen hundred metric tons, well over a thou-

sand tons is engine.

Now you know why there aren’t any space yachts

flitting around out here. Slinger’s one of the smallest ships

in commission, and she’s bloody big. If Jan and I hadn’t

happened to hit lucky by being the only possible buyers

for a couple of wrecks, and hadn’t had friends at

Barclay’s who thought we might make a go of it, we’d

never have owned our own ship.

When I tell people about the engines, they don’t ask

what we do aboard Slinger when we’re on long pas-

sages, but they’re only partly right. You can’t do any-

thing to an engine while it’s on. It either works or it

doesn’t, and all you have to do with it is see it gets fed.

It’s when the damned things are shut down that the

work starts, and that takes so much time that you make

sure you’ve done everything else in the ship when you

can’t work on the engines. There’s a lot of maintenance,

as you might guess when you think that we’ve got to

make everything we need, from air to zweiback. Living

in a ship makes you appreciate planets.

Space operations go smooth, or generally they don’t

go at all. I looked at Jan and we gave each other a

quick wink. It’s a good luck charm we’ve developed.

Then I hit the keys, and we were off.

It wasn’t a long boost to catch up with Agamemnon.

I spent most of it in the contoured chair in front of the

control screens. A fifth of a gee isn’t much for dirtsiders,

but out here it’s ten times what we’re used to. Even the

cats hate it.

The high gees saved us on high calcium foods and

the drugs we need to keep going in low gravs, and of

course we didn’t have to put in so much time in the

exercise harnesses, but the only one happy about it

was Dalquist. He came up to the control cap about an

hour out from Jefferson.

“I thought there would be other passengers,” he said.

“Really? Barbara made it pretty clear that she wasn’t

interested in Pallas. Might go to Mars, but—”

“No, I meant Mr. Hornbinder.”

“He, uh, seems to have become ill. So did his friends.

Happened quite suddenly.”

Dalquist frowned. “I wish you hadn’t done that.”

“Really? Why?”

“It might not have been wise, Captain.”

I turned away from the screens to face him. “Look,

Mr. Dalquist, I’m not sure what you’re doing on this

trip. I sure didn’t need Rhoda’s goons along.”

“Yes. Well, there’s nothing to be done now in any

event.”

“Just why are you aboard? I thought you were in a

hurry to get back to Marsport—”

“Butterworth interests may be affected, Captain. And

I’m in no hurry.”

That’s all he had to say about it, too, no matter how

hard I pressed him on it.

I didn’t have time to worry about it. As we boosted,

I was talking with Agamemnon. She passed about half a

million kilometers from Jefferson, which is awfully close

out here. We’d started boosting before she was abreast

of the rock, and now we were chasing her. The idea was

to catch up to her just as we matched her velocity. Mean-

while, Agamemnon’s crew had their work cut out.

When we were fifty kilometers behind, I cut the en-

gines to minimum power. I didn’t dare shut them down

entirely. The fusion power system has no difficulty with

restarts, but the ion screens are fouled if they’re cooled.

Unless they’re cleaned or replaced we can lose as much

as half our thrust—and we were going to need every

dyne.

We could just make out Agamemnon with our tele-

scope. She was too far away to let us see any details. We

could see a bright spot of light approaching us, though:

Captain Jason Ewert-James and two of his engineering

officers. They were using one of Agamemnon’s scooters.

There wasn’t anything larger aboard. It’s not prac-

tical to carry lifeboats for the entire crew and passenger

list, so they have none at all on the larger boostships.

Earthside politicians are forever talking about “requir-

ing” lifeboats on passenger-carrying ships, but they’ll

never do it. Even if they pass such laws, how could they

enforce them? Earth has no cops in space. The U.S.

and Soviet Air Forces keep a few ships, but not enough

to make an effective police force even if anyone out

here recognized their jurisdiction, which we don’t.

Captain Ewert-James was a typical ship captain.

He’d formerly been with one of the big British-Swiss

lines and had to transfer over to Pegasus when his

ship was sold out from under him. The larger lines like

younger skippers, which I think is a mistake, but they

don’t ask my advice.

Ewert-James was tall and thin, with a clipped mus-

tache and greying hair. He wore uniform coveralls over

his skintights, and in the pocket he carried a large pipe

which he lit as soon as he’d asked permission.

“Thank you. Didn’t dare smoke aboard Agamem-

non—”

“Air that short?” I asked.

“No, but some of the passengers think it might be.

Wouldn’t care to annoy them, you know.” His lips

twitched just a trifle, something less than a conspirator’s

grin but more than a deadpan.

We went into the office. Jan came in, making it a bit

crowded. I introduced her as physician and chief officer.

“How large a crew do you keep, Captain Kephart?”

Ewert-James asked.

“Just us. And the kids. My oldest two are on watch at

the moment.”

His face didn’t change. “Experienced cadets, eh? Well,

212

we’d best be down to it. Mr. Haply will show you what

we’ve been able to accomplish.”

They’d done quite a lot. There was a lot of ex-

pensive alloy bar-stock in the cargo, and somehow they’d

got a good bit of it forward and used it to brace up the

bows of the ship so she could take the thrust. “Haven’t

been able to weld it properly, though,” Haply said. He

was a young third engineer, not too long from being a

cadet himself. “We don’t have enough power to do weld-

ing and run the life support too.”

Agamemnon’s image was a blur on the screen across

from my desk. It looked like a gigantic hydra, or a bull-

whip with three short lashes standing out from the han-

dle. The three arms rotated slowly. I pointed to it

“Still got spin on her.”

“Yes.” Ewert-James was grim. “We’ve been running

the ship with that power. Spin her up with attitude jets

and take power off the flywheel motor as she slows down.”

I was impressed. Spin is usually given by running a big

flywheel with an electric motor. Since any motor is a

generator, Ewert-James’s people had found a novel way to

get some auxiliary power for life-support systems.

“Can you run for a while without doing that?” Jan

asked. “It won’t be easy transferring reaction mass if you

can’t.” We’d already explained why we didn’t want to

shut down our engines, and there’d be no way to supply

Agamemnon with power from Slingshot until we were

coupled together.

“Certainly. Part of the cargo is liquid oxygen. We can

run twenty, thirty hours without ship’s power. Possibly

longer.”

“Good.” I hit the keys to bring the plot tank results

onto my office screen. “There’s what I get,” I told them.

“Our outside time limit is Stinger’s maximum thrust. I’d

make that twenty centimeters for this load—”

“Which is more than I’d care to see exerted against

the bows, Captain Kephart. Even with our bracing.”

Ewert-James looked to his engineers. They nodded

gravely.

“We can’t do less than ten,” I reminded them. “Any-

thing much lower and we won’t make Pallas at all.”

“She’ll take ten,” Haply said. “I think.”

The others nodded agreement. I was sure they’d been

over this a hundred times as we were closing.

I looked at the plot again. “At the outside, then, we’ve

got one hundred and seventy hours to transfer twenty-

five thousand tons of reaction mass. And we can’t work

steadily because you’ll have to spin up Agamemnon for

power, and I can’t stop engines—”

Ewert-James turned up both corners of his mouth at

that. It was the closest thing to a smile he ever gave. “I’d

say we best get at it, wouldn’t you?”

Agamemnon didn’t look much like Slingshot. We’d

closed to a quarter of a klick, and steadily drew ahead

of her; when we were past her, we’d turn over and

decelerate, dropping behind so that we could do the

whole cycle over again.

Some features were the same, of course. The engines

were not much larger than Slingshot’s and looked much

the same, a big cylinder covered over with tankage and

coils, acceleration outports at the aft end. A smaller tube

ran from the engines forward, but you couldn’t see all of

it because big rounded reaction mass canisters covered

part of it.

Up forward the arms grew out of another cylinder.

They jutted out at equal angles around the hull, three

big arms to contain passenger decks and auxiliary sys-

tems. The arms could be folded in between the reaction

mass canisters, and would be when we started boosting.

All told she was over four hundred meters long, and

with the hundred-meter arms thrust out she looked like

a monstrous hydra slowly spinning in space:

“There doesn’t seem to be anything wrong aft,” Buck

Dalquist said. He studied the ship from the screens, then

pulled the telescope eyepiece toward himself for a direct

look.

“Failure in the superconductor system,” I told him.

“Broken lines. They can’t contain the fusion reaction long

enough to get it into the MHD system.”

He nodded. “So Captain Ewert-James told me. I’ve

asked for a chance to inspect the damage as soon as it’s

convenient.”

“Eh? Why?”

“Oh, come now, Captain.” Dalquist was still looking

through the telescope. “Surely you don’t believe in

Rhoda Hendrix as a good luck charm?”

“But—”

“But nothing.” There was no humor in his voice, and

when he looked across the cabin at me, there was none

in his eyes. “She bid far too much for an exclusive char-

ter, after first making certain that you’d be on Jefferson

at precisely the proper time. She has bankrupted the

corporate treasury to obtain a corner on deuterium.

Why else would she do all that if she hadn’t expected

to collect it back with profit?”

“But—she was going to charge Westinghouse and Iris

and the others to boost their cargo. And they had cargo

of their own—”