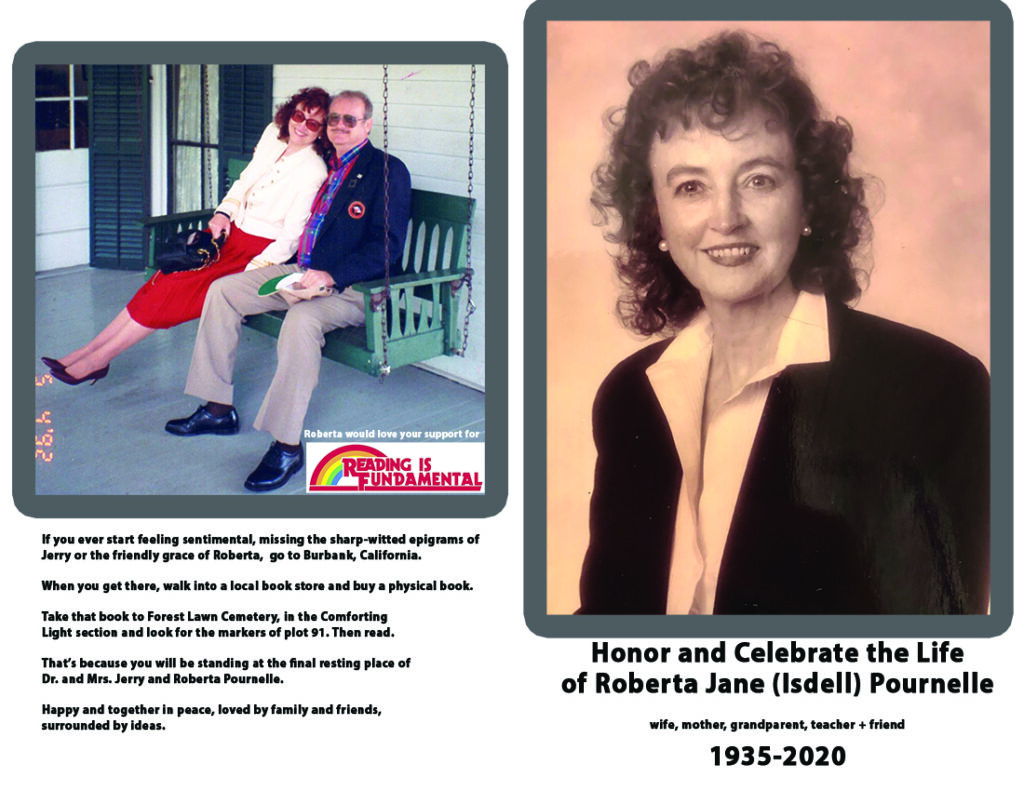

Roberta Jane Isdell Pournelle

16 June 1936–3 August 2020

By Jennifer R. Pournelle

A life as full and rich as this, with so much family; so many friends; so many colleagues; so many in attendance across the interverse, is not done justice in any speech of a length to which many people are prepared to listen. I mulled on this waking and sleeping, but not until I took a walk with our dog, in the late evening heat of summer, a chorus of swallows swirling overhead, did I hear in them a reminder of what I remember most of her over my lifespan of 60+ years.

A life as full and rich as this, with so much family; so many friends; so many colleagues; so many in attendance across the interverse, is not done justice in any speech of a length to which many people are prepared to listen. I mulled on this waking and sleeping, but not until I took a walk with our dog, in the late evening heat of summer, a chorus of swallows swirling overhead, did I hear in them a reminder of what I remember most of her over my lifespan of 60+ years.

Those memories bracket two spans of my life, condensed to vignettes that, I think, spell out what she was to me, and to so, so many others.

My earliest memory is partly my own; partly reconstructed from bits and pieces told me over the years by all of those no longer with us. I was not yet three years old. Stephen, my infant baby brother; my father’s first son, abruptly died. We all were devastated, but my own mother, at twenty-two years so unprepared and crushed with grief, had nothing left to give a lad who had himself just turned twenty- four. Agonized by loss, she left, leaving him with no-one, either. His best mate moved in to share the house, and I often went to visit. He was very sad. He was never really there.

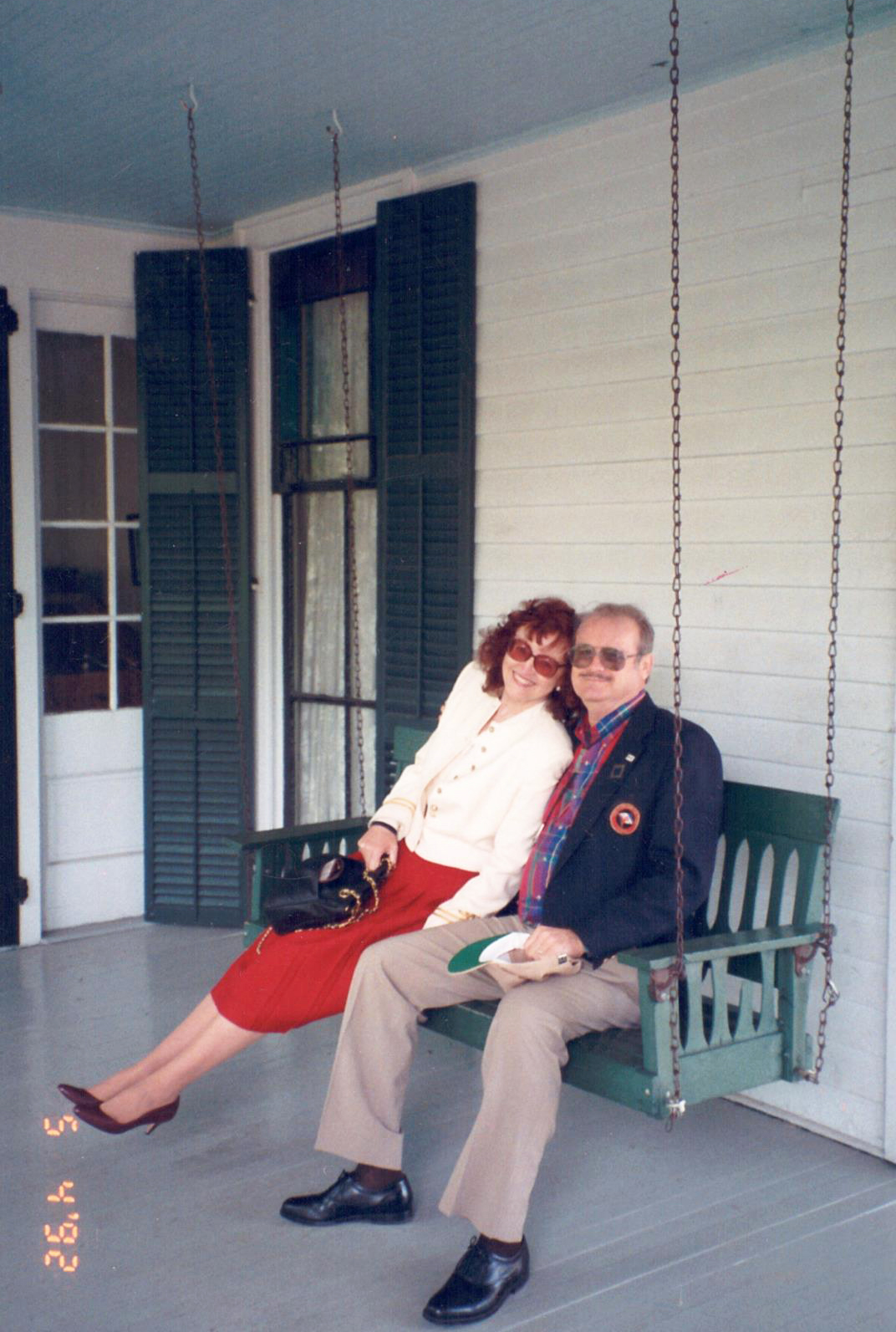

But Roberta was. A fiery redhead, who drove racecars and climbed mountains, breathed life back into his void. He came alive. We came alive. We saw life anew,

because she was there.

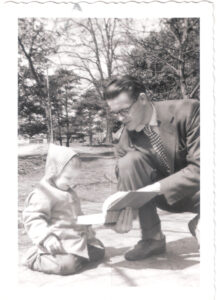

That did not happen all at once. Perhaps I was a reminder. Perhaps he had to prove his worth. Perhaps he knew no better. But to see him then required an appointment. It required me to dress my best, and be my quietest, and slowly climb those monstrous stairs. There were only actually six of them, and then a turning, and then three more. And him, his pipe, his study desk. His grave concern. His nod, and then dismissal. All in order. All correct.

And at three, or four, or five (my age I can’t remember), all terrifying. Sad, you think? No, not at all. Because I remember her hand, warm upon my shoulder. I remember her voice, murmured in my ear, making me stand tall and true and brave with excitement. I remember her grasping my own hand, leading me down the stairs, where warm cookies and milk were waiting.

Because she was there

And by 1961, when I was six, I had a new little brother. His baby eyes, and baby hair, and baby hands were just like baby Stephen’s. I loved him on sight. I was terrified on sight. I was afraid to look; afraid to touch; afraid to kiss his baby forehead. I was afraid to hurt him. Afraid I’d break him. Afraid it all would be over again.

“Peas,” she said. “You are like peas in a pod.” I stared and stared. And out of the blue, she simply said, “whistle him a tune.” I was, at six, after seeing Disney’s Snow White, rather whistling-obsessed. That did it. I whistled a happy tune. And taught Alex to whistle. Because she was there.

Summer writing workshop.

I won’t rose-tint it. Girls are programmed, by nature or nurture, to come to resent their stepmothers. Stepmothers are different. Their rules are different. And when push comes to shove, a screwed-up face punctuated by “You aren’t my real Mom!” works wonders.

But we look back with maturity. And realize now that, what seemed agony then, was done with the best of intentions. I remember one visit—a long, summer visit, when Mom was away, and Dad was away, in pursuit of professional success, and only me and Alex were left—Roberta seeing my report card. All A’s, except for that D in handwriting.

What followed was anathema. Forced to sit at the kitchen table, drilling my letters in penmanship. But, of course, Roberta understood what I, in my third-grade-or-so head could not: In those days and times, I could race NASA to the moon. But, I was a girl. And, as a girl, if my handwriting was illegible, nobody would give my words a second chance. That summer morning spent in purgatory was never meant as punishment. It was meant as enablement. She didn’t like it any more than I did, but she was a teacher, and she was there.

That was early childhood. Skip forward through the years, and I am a young graduate student who has long since lost touch with my California family. I see Dad on an obscure TV show, then find a bank of national phone books in our university library (to the old among you: remember phone books?). I find and dial the numbers. A male voice answers. In that split-second, I realize what age Alex must be. What age Frank must be. I don’t know who has answered. My first reaction? With nary a moment’s thought or hesitation?

“Is Roberta there?” And her reaction? With nary a moment’s thought or hesitation? “Oh my God, Jenny! Hang on! Let me go get your father!” Neither of us hesitated or doubted. I most certainly waivered. But she did not, not for an instant.

Because she was there.

Other People’s Children.

I was hardly an “only child,” and I’m not merely referring to my wonderful brothers. Roberta taught in schools where most would not. She taught kids who were guilty of being poor, or black, or Latinx, or homeless. or abused, or dyslexic, or otherwise illiterate and/or desperate. Kids with “form,” kids with little future; kids who were pregnant or fathers or incarcerated for crimes real or imagined and precious little hope of anger management. The kids nobody wanted. The kids dismissed as “juvvies.” The kids about whom precious few truly, actually, cared.

Advised to leave, advised to cease, advised that her talents lay elsewhere, she taught on. She was there.

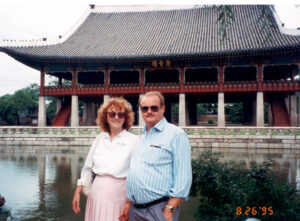

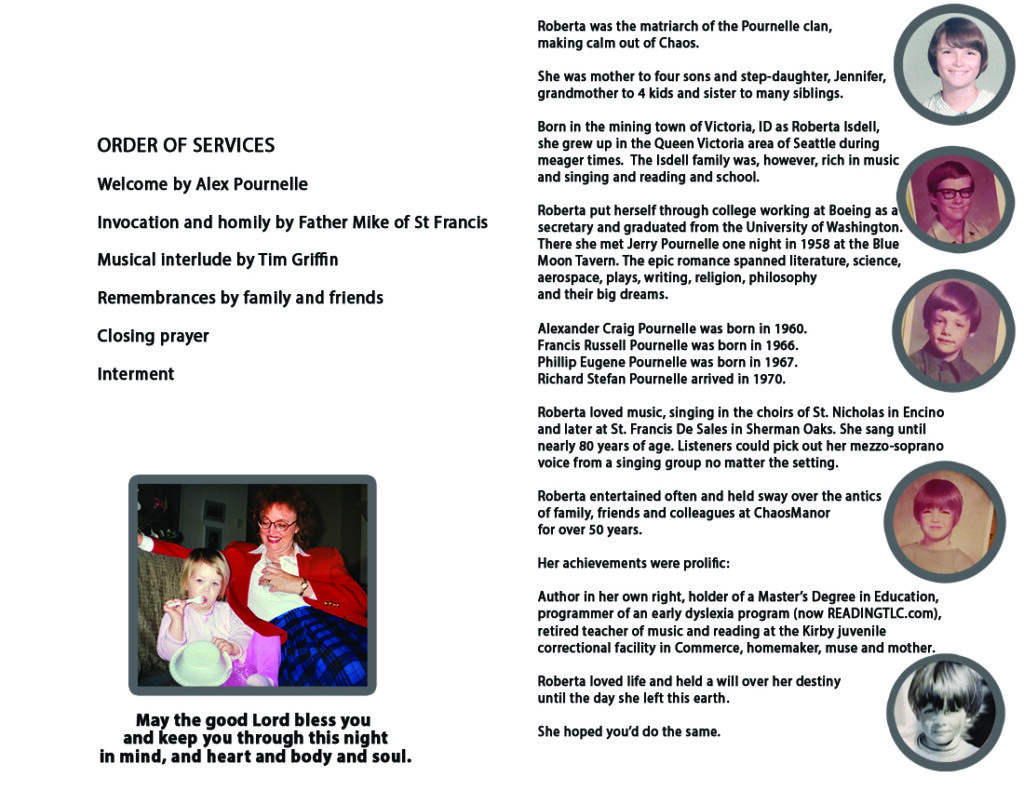

Years flew by. Thanksgivings, Christmases, Easters: what little time I had or could steal from deployments and stationings and duties in distant parts, my new home on the California coast was always there. The table was never empty. Fans and friends; purveyors of incredible schemes; business partners and family help: all had a place, all were welcomed; all were served up; and we were all recruited to cook or wash or dry or, at bare minimum, show up. We hiked in the hills with a succession of dogs. I marveled at her command of Spanish laced with Mayan. Those of you who have never been road warriors; who have never borne the grind of a new home every year, or two, or three, cannot imagine the blessing. The relief. The  rejuvenation. The joy that comes of returning to a home. And it was a home. A home filled with light and joking and music. “Jerry,” she’d say, throwing an arm around me as he cuddled a kitten or a remote control, “hug your son.” Because, she was there.

rejuvenation. The joy that comes of returning to a home. And it was a home. A home filled with light and joking and music. “Jerry,” she’d say, throwing an arm around me as he cuddled a kitten or a remote control, “hug your son.” Because, she was there.

Family and Friends.

Roberta’s kids

I cannot speak for “the boys”–all those men who are my brothers by blood and by affiliation– or, as I’ve said, mostly I was either too young or too old to be much more than glancingly involved in the everyday triumphs and struggles and mysteries and joys; the crushing disappointments and outlandish hopes that make up daily family life in every family, everywhere. So, of those times, I leave them to speak of her for themselves.

But one thing I do know; one thing I witnessed again, and again, and again. For every single one of them, and for that biggest boy there ever was in her life (the lifetime project that was my father), time and again; (almost) every moment; (almost) every hour:

She was there.

AfterWord

And so, as we say our farewells here today, I have no doubt that when our own times come, greeted by a chorus of angels, she will firmly grasp our hands and march us though St Peter’s gates. No question. No doubt. She’ll be there.

I love you Roberta, and have done all these more-than-60-years. I wish we’d had more time together, not just at visits and reunions and homecomings and bedsides, especially over these past few years, and especially at the end—

—so that I could have said to you, in person; could have whispered in your ear:

“Gurl, go party with the cherubim. You’ve earned it. You’ve always been there.”

I’ll see you then.

Jenny

The eulogy made me cry. Anyone from a loving family can relate.

Yes I cried. Thank you for sharing this.

A wonderful tribute to a wonderful lady. Thank you Jennifer!

The last two lines certainly sum it up. A beautiful Eulogy.

Perhaps I’m denser than neutronium, but I don’t quite understand where Jennifer fits in the Pournelle genealogy. Wikipedia is not helpful. I loved Jennifer Pournelle’s novel OUTIES.

I never communicated with Mrs Pournelle unless perhaps Jerry shared one of my irritating emails. However; she must have been quite a lady to manage the Pournelle clan.

I’m the oldest of Jerry’s children – born 1955 in Seattle, WA, the daughter of his first wife, Mary Belle Siemen. So glad you enjoyed Outies!

Now that was beautiful. May their eternity be together.

SIMPLY WONDERFUL…

Beautifully written.

“Teacher”

I was one of those who purchased a copy of her reading program. It worked.

Thank you, Mrs. Pournelle.

Starting back in the 1980s I read Jerry’s work in paper magazines, books, and latterly online, he was a constant daily go-to place for things of interest whether science fiction, fact, technology, politics and much more. Roberta was always present in his online daily writing, very much there as a part of Jerry’s world. My life is poorer for their passing. I did not know until now that he was married before, lost an infant son tragically and also as a result of this tragedy his first wife. I’m glad Roberta was there for him after that. Thanks for writing this Jennifer and it made me cry too.

Thanks to you all for your very kind words. I miss her tremendously – every day, in different ways. I glad that in her later years we managed a bit of time to be “just us girls.”